THE HUNGARIAN PRINCESS: MARIE VALERIE

Why was an Austrian Archduchess forced to talk in Hungarian and use this language as a mother tongue?

Born by a Bavarian mother and an Austrian father Marie Valerie was brought up as a Hungarian princess. Although her mother tongue was German, her first language was Hungarian and it was the one she used while talking to her mother, Queen Elisabeth and her father, King Franz Joseph. Archduchess Marie Valerie of Austria (22 April 1868 – 6 September 1924) was the fourth and last child of Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria and Elisabeth of Bavaria. Her given name was Marie Valerie Mathilde Amalie but she was usually called Valerie.

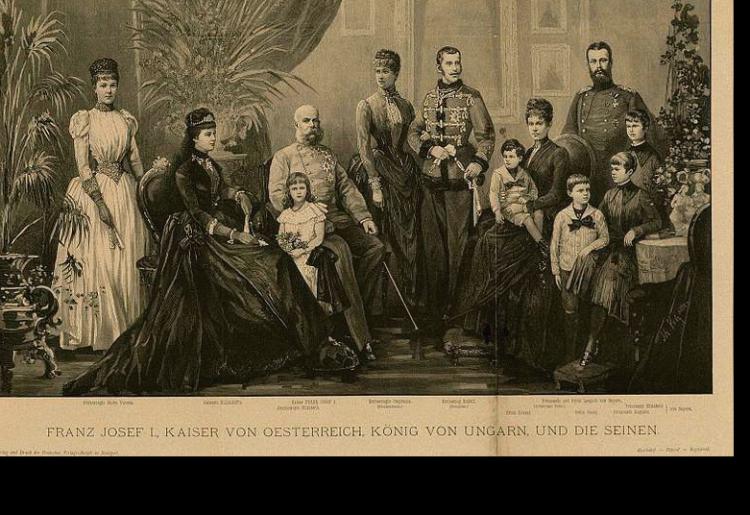

Drawing of the Royal Family (1883): Princess Marie Valerie; Queen Elisabeth; Elisabeth, Rudolph’s daughter in front of Franz Joseph I; Crown Prince Rudolf with his wife, Stephanie ; Princess Gisela with her husband, Leopold and their children

Marie Valerie, Sisi’s fourth child was born in Hungary in 1868. She was deliberately called the “Hungarian Princess” by Queen Elisabeth. The Viennese also called Valerie like this but they did it ironically. The girl, of course, according to Elisabeth’s instruction, was allowed to speak to her parents in Hungarian and she could learn to speak her mother tongue, German, only later. The Queen (Empress Elisabeth) had hoped for giving birth to a son and being able to give a king to the Hungarians that was why she decided to have her labour in our country, Hungary. However, to the greatest relief of the Viennese, Elisabeth gave birth to a girl, who she named Marie Valerie. Not only in Gödöllő but also in the Viennese Imperial Court in Austria, the little princess was taught in Hungarian. She received Hungarian education from the Hungarian Countess Korniss and Bishop Hyacinth Ronay, the latter was also asked to pray with Valerie in Hungarian. Due to all these facts the girl was called both by the Viennese and our people the “Hungarian Princess”. Photo: Little Princess Marie Valerie

Marie Valerie liked to donate from her early childhood. In the Royal Palace of Gödöllő a lot of sweets were waiting for her on the table after dinner and she could take as much as she wanted to. Of course, Valerie took a lot from them. The Queen was said to tell her daughter the following words: "Thus, took aside half of it, and in the afternoon when you go for a walk, give them to the poor children you meet. You'll see how much they will like it!" Valerie did so, and the children in Gödöllő were accustomed to receiving delicious sweets from the little princess. Whenever they saw Valerie, they ran happily towards her carriage shouting: "Here comes Valerie!" Before a Christmas holiday Marie Valerie asked money instead of presents saying that she would give that to the Hungarian children. So small bags containing new silver forint coins were hanging down the branches of the royal Christmas tree. The children were gathering as usual at Christmas (on 24th), which was Queen Elisabeth's birthday too, hoping to get from the royal sweets. The greater the joy was when they saw that Valerie was not only handing out sweets but also money bags.

Royal dainties and gifts were given to the children when the Queen and her daughter stayed in Gödöllő. Elisabeth’s “name day” (in Hungary, each person has a “name day” but not everyone celebrates their own ones, however, most of us do so) was held in Gödöllő at the time, and it was a celebration for the whole settlement.

However, then Marie Valerie might not have dared to admit even to her leather-bound diary how much she wanted to speak to her parents in her own mother tongue. Later, she asked her father secretly to speak to her in German. However, she never dared to talk about her desire with her beloved mother.

As an adult, Princess Valerie continued the charity work even towards us (Hungarians) until her death. After her marriage she took the complete conceptual furniture from her bedroom of the Royal Palace of Gödöllő to her new home in the German Wallsee. The people in Gödöllő believed that this reflected the princess’s love towards them and their settlement. The truth is much simpler. The reason must have been rooted more in her love towards her mother, Queen Elisabeth than in Hungarians. This anecdote, however, still has been living in the memory of our people.

IN HUNGARIAN: A GÖDÖLLŐI KIRÁLYKISASSZONY

WORKS CITED: Brigitte Hamann: The Reluctant Empress. Source of the anecdote: The anecdote (about the sweets and the silver coins) was written by using Ferenc Ripka, Queen Elisabeth in Gödöllő, memorial book (1901). Royal family photo: www.dorotheum.com